Winning Evaluation Strategies for Smaller Nonprofits

The following post was written by Standards for Excellence Licensed Consultant Elizabeth Galaida and is part of our “Ten Years of Advancing Excellence” blog series, celebrating ten years of the Standards for Excellence Licensed Consultant program. Elizabeth Galaida is a career nonprofit specialist that offers strategic planning assistance and database renovation. Bringing the necessary depth and breadth of skills sets to bear, she specializes in helping small to mid-sized nonprofits grow and thrive. Elizabeth became a Standards for Excellence Licensed Consultant in 2014.

The following post was written by Standards for Excellence Licensed Consultant Elizabeth Galaida and is part of our “Ten Years of Advancing Excellence” blog series, celebrating ten years of the Standards for Excellence Licensed Consultant program. Elizabeth Galaida is a career nonprofit specialist that offers strategic planning assistance and database renovation. Bringing the necessary depth and breadth of skills sets to bear, she specializes in helping small to mid-sized nonprofits grow and thrive. Elizabeth became a Standards for Excellence Licensed Consultant in 2014.

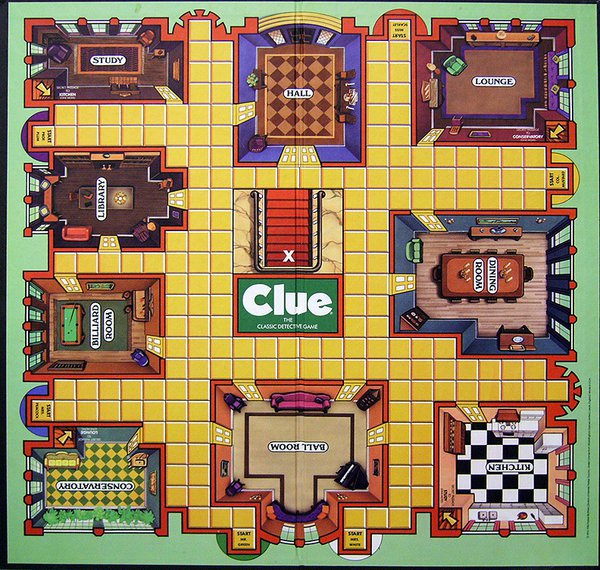

When my son was little, we played a board game called Clue, Jr. The Jr. version is similar to the classic Clue game, but relies on a simple, straightforward process of elimination to solve a simple mystery. The adult version is best played by controlling for both known and unknown variables, using complex, two-step logic, and putting on a good poker face—there, I’ve just given away my game-winning secrets.

When it comes to program evaluation and demonstrating nonprofit impact, small organizations are often asked by funders to play the full version of Clue on a Clue, Jr. budget. Grant makers seeking to determine whether their $5,000 grant was “impactful” ask questions of their grantees that require $100,000 worth of randomized control trials to answer completely. That leads many smaller nonprofits to assume that they simply can’t show impact. The reality is that smaller nonprofits can, and should, be evaluating their programs, but they need to be asking different questions.

Those highest up on the spectrum of scholarly nonprofit research generally seek to establish scientific causality between a given program and its desired outcomes, commonly discussed as “evidence-based practices.” While few funders demand this level of sociological research of their grantees—and even fewer are ready to pay for it—there does seem to be an expectation among many that even small nonprofits should somehow “prove” the direct impact of their programs.

In the end, what usually happens is that the nonprofit cobbles together a report based largely on output data, the grant maker files it, and the discussion is over. However, the Standards for Excellence Institute has long held that all nonprofits can and should strive for excellence and impact, regardless of size. Evaluation for smaller nonprofits can be both effective and cost-effective, so long as the evaluation is mission-focused, includes quantitative and qualitative data, includes participant input and determines whether the programs answer a community need.

An organization’s program evaluation should start first and foremost with the mission. The Standards for Excellence state that nonprofits

“…should have a well-defined mission, and its programs should effectively and efficiently work toward achieving that mission.”

It is hard to argue that smaller nonprofits need major funding in order to accomplish this. Your board should review the mission statement annually, with newer board members bringing fresh perspectives on whether or not it is “well-defined.”

Your mission statement should be specific enough to know whether or not you are achieving it. The board should review all programs annually to determine if they are mission-focused or not. “Mission creep” is a common threat to the effectiveness and sustainability of an organization, diverting precious resources away from where they should be going.

In order to meet the Standards for Excellence, any program evaluation, whether conducted by committed volunteers or a national think tank, should include both quantitative and qualitative data (at the Basics level, data collection should have begun) and include input from program participants.

Quantitative data—“the numbers”—help us see the bare bones realities of our programs. Our brains lie to us all the time. It’s called confirmation bias. We tend to see only the facts that confirm our already-established beliefs. However, the numbers can tell us a different story, one that we may not want to hear. For example, if the graduation rate of your financial literacy program is only half that of similar programs, that number will prompt you to find out why, so you can serve your students better. Qualitative data provides context and meaning for your quantitative numbers. If the financial literacy organization in the above example discovered through participant surveys that the timing of the program made it very difficult for single parents to attend classes, a simple change of class time could lead to higher graduation rates. Which, of course, is also better mission fulfillment and better service to people in need.

Organization staff should build both qualitative and quantitative data collection into their regular, daily activities. That may mean tracking only how many people come through the door, or it may also mean this:

-

Demographics

-

Achievement, graduation or completion rates

-

Changes in knowledge or confidence

-

Satisfaction ratings

A cost-effective means of collecting qualitative data and getting participant input is to conduct exit interviews or surveys with your constituents. Make a point to ask constituents frequently for feedback, or schedule feedback collection to occur at program milestones.

Regarding the means of data collection, small nonprofits should remember that the more informal the data collection, the more human time it takes to compile the results. If you have a pile of ticket stubs of differing colors from one concert to count and sort, this is not terribly taxing—until you have to do this five times per week. This is where a scanning device to determine what kinds of tickets were used (such as full price, senior, educational, special groups, etc.) might be worth the expense. For organizations with complex services, or for those with state and federal reporting requirements for specific individuals over time, a database is a must.

Organizations should regularly evaluate the need for their programs. In my staff reviews of accreditation applications, this is the one area of evaluation that organizations frequently overlook. Waiting lists, sold out concerts, and requests from the public and partner service providers are all valid examples of the evidence of need for your programs. Nonprofits should be careful to define “need” in terms of their constituents, and not in terms of what funders want to pay for.

The conversation on nonprofit impact is constantly changing, and some researchers are starting to recognize that nonprofits may operate on a spectrum of best practices that range from “performance measurement” to “evaluation.” Whatever your nonprofit calls it, you can be successful in determining if your programs are meeting your mission, your expectations of quality and the community’s needs.

Read Further:

As Nonprofit ‘Research’ Proliferates, It Must Be Viewed With Healthy Skepticism

Three Kinds of Data that Actually Matter to Nonprofits

Tools and Resources for Assessing Social Impact

Performance Measurement and Management, from Urban Institute’s Measure 4 Change